This is not an attempt to investigate or even to come to grips with what Josh Duggar has done. I am not a person who watches reality shows, let alone watches religious reality shows--with the exception of early episodes of Amish Mafia; that shit was dope--and I have no dog in the fight over whether companies should or should not continue to sponsor their show. If they do, it will make absolutely no difference to anyone; if they don't, the show will fade from memory and, again, make absolutely no difference to anyone.

What this is is an attempt to answer a question I came across on the Facebook page of a progressive religious group I belong to. A correspondent wrote that he had been reading 1 Corinthians and quoted from it: "But now I am writing to you that you must not associate with anyone who claims to be a brother or sisterc but is sexually immoral or greedy, an idolater or slanderer, a drunkard or swindler. Do not even eat with such people." Then the poster asked for people's thoughts on the passage in relation to the disclosures about Josh Duggar.

There were many thoughtful and considered responses, most of them very long and complex. But it struck me that, in its refutation of most of the synoptic messages of Jesus, Paul was denying one of the very things that made the synoptic Jesus so different: that is, that he would associate with people who were, exactly as Paul describes, "sexually immoral, or greedy, an idolater or slanderer, [or] a drunkard or swindler." The Jesus we read about in the gospels, whether he is the historical Jesus or a composite of many Jesus-figures or the creation of an especially gifted writer, is unique among the religous people we know of at that time and place, not only allowing these sinners to eat and be with him, but in some cases actively seeking them out, and in the case of the woman caught in adultery putting himself at risk to save her.

Now the traditional theological response in favor of keeping this division, thereby accepting and building upon the Paul command, is that the difference is that the people Jesus associated with had repented of their sinful lives and so were "worthy" of being with him. But that certainly isn't the case with, for instance, the woman caught in adultery: she's had no prior association with Jesus we're told of, and while it's possible in the small world of First Century Jerusalem that the woman knew of Jesus' reputation, he wouldn't have known her. And while it's also true she repents of her past at the end of the tale, that is after Jesus places his own reputaiton, and possibly his life, in question by responding as he does.

So it doesn't matter, in this reading, whether Josh Duggar repents his actions. The Jesus of the gospel stories, if he were asked to sit and eat with him, would have done so. Like Jesus, I also believe in the essential dignity of every person, and while I haven't been asked, I could do no less.

Wednesday, May 27, 2015

Monday, May 11, 2015

when we are most ourselves

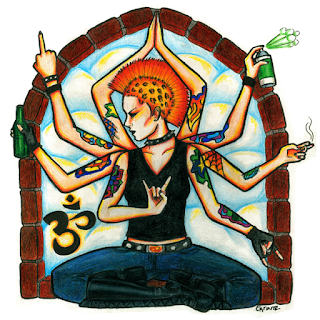

My interest and faith in punk and punks is a theme on this blog, as is my attempts to articulate a definition of a punk spirituality. This musician/teacher, Miguel Chen of Teenage Bottlerockets, has gone me one better by creating this short documentary about the interconnectivity of punk and yoga. And while yoga is not my practice, I recognize, in the same way Christianity is for others, it is a potent path. To say I'm in awe of this motherfucker is to downplay the jealousy I feel.

Labels:

appreciation,

beloved community,

cult of personality,

movies,

music,

practice,

punk,

radicality,

religions,

rituals

Monday, May 4, 2015

as we watch Baltimore burn

I have been in Baltimore a handful of times, usually on my way somewhere else. I don't think I've spent more than a day there. Most everything I know about the city comes from the novels of Anne Tyler. And the Baltimore she writes about, needless to say, is not the Baltimore of Freddie Gray.

But I'm not an impartial third party either, insofar as I believe we can and should live in a single, worldwide beloved community. My recognition that we don't isn't an admission to the impossibility of the dream, only of our unwillingness to accomplish it. And I know if my city was aflame, I'd certainly want other people caring about it.

I read this essay by Brittney Cooper several days ago and it won't let me go. Try as will to understand the positions of the three black women who are the official faces of Baltimore-Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, it's mayor; General Linda Singh, of the Maryland National Guard; and just-confirmed Attorney General Loretta Lynch-indeed, even to commiserate with them (as she writes, "Not one of these women stands in the place of power she stands in without having battled for it"), she ends up recognizing that "American empire, in its most democratic iteration, is no respecter of persons. Any person willing to do the state's bidding can have a role to play." Cooper locates the sound of the shattering of the peace among the poor and disenfranchised of Baltimore in the sound of the snapping of Freddie Gray' s neck.

That is a horrible metaphor. It is also resolutely true and it's in the truth of it that the horror lies. No one in my community ought to be familiar with that sound.

More troubling has been the response of strangers, and even some people I know, to the riot in Baltimore as if Freddie Gray's death is excused because of the reactions to it. As if Baltimore police were somehow punishing him in advance for the temerity to ignite the CVS with his death.

The simple truth of the situation is that Freddie Gray should not have died. I contend he should not have been arrested in the first place, but even if we grant he had committed a crime, including murder, there is no reason for any person to die in police custody. To quote the character ML from the great Do the Right Thing, a film whose subject, the death of a young black man while being arrested, should not be nearly as contemporary twenty-five years later as it is: "It's as plain as day. They didn't have to kill the boy."

But most troubling is the epiphany I have come to. If I was in Baltimore would I join the riots and looting? And the answer is yes. Yes, I would. Not because there are things I want but that there are things I don't want. I don't want predatory lending in my neighborhood. I don't want a military presence in my neighborhood. I don't want to be called a thug when I strike back against a system that threatens me and my future. I don't want police killing anyone whose most criminal act is running away from them. And because of where I live and who I am, or specifically who I am not, I don't experience any of that.

Neither should anyone else. It's as plain as day.

But I'm not an impartial third party either, insofar as I believe we can and should live in a single, worldwide beloved community. My recognition that we don't isn't an admission to the impossibility of the dream, only of our unwillingness to accomplish it. And I know if my city was aflame, I'd certainly want other people caring about it.

I read this essay by Brittney Cooper several days ago and it won't let me go. Try as will to understand the positions of the three black women who are the official faces of Baltimore-Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, it's mayor; General Linda Singh, of the Maryland National Guard; and just-confirmed Attorney General Loretta Lynch-indeed, even to commiserate with them (as she writes, "Not one of these women stands in the place of power she stands in without having battled for it"), she ends up recognizing that "American empire, in its most democratic iteration, is no respecter of persons. Any person willing to do the state's bidding can have a role to play." Cooper locates the sound of the shattering of the peace among the poor and disenfranchised of Baltimore in the sound of the snapping of Freddie Gray' s neck.

That is a horrible metaphor. It is also resolutely true and it's in the truth of it that the horror lies. No one in my community ought to be familiar with that sound.

More troubling has been the response of strangers, and even some people I know, to the riot in Baltimore as if Freddie Gray's death is excused because of the reactions to it. As if Baltimore police were somehow punishing him in advance for the temerity to ignite the CVS with his death.

The simple truth of the situation is that Freddie Gray should not have died. I contend he should not have been arrested in the first place, but even if we grant he had committed a crime, including murder, there is no reason for any person to die in police custody. To quote the character ML from the great Do the Right Thing, a film whose subject, the death of a young black man while being arrested, should not be nearly as contemporary twenty-five years later as it is: "It's as plain as day. They didn't have to kill the boy."

But most troubling is the epiphany I have come to. If I was in Baltimore would I join the riots and looting? And the answer is yes. Yes, I would. Not because there are things I want but that there are things I don't want. I don't want predatory lending in my neighborhood. I don't want a military presence in my neighborhood. I don't want to be called a thug when I strike back against a system that threatens me and my future. I don't want police killing anyone whose most criminal act is running away from them. And because of where I live and who I am, or specifically who I am not, I don't experience any of that.

Neither should anyone else. It's as plain as day.

Labels:

Baltimore,

beloved community,

death,

Freddie Gray,

killing,

law,

media,

occupy,

poverty,

protest,

radicality,

witnessing

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)